when you want, where you want.

CJ Television

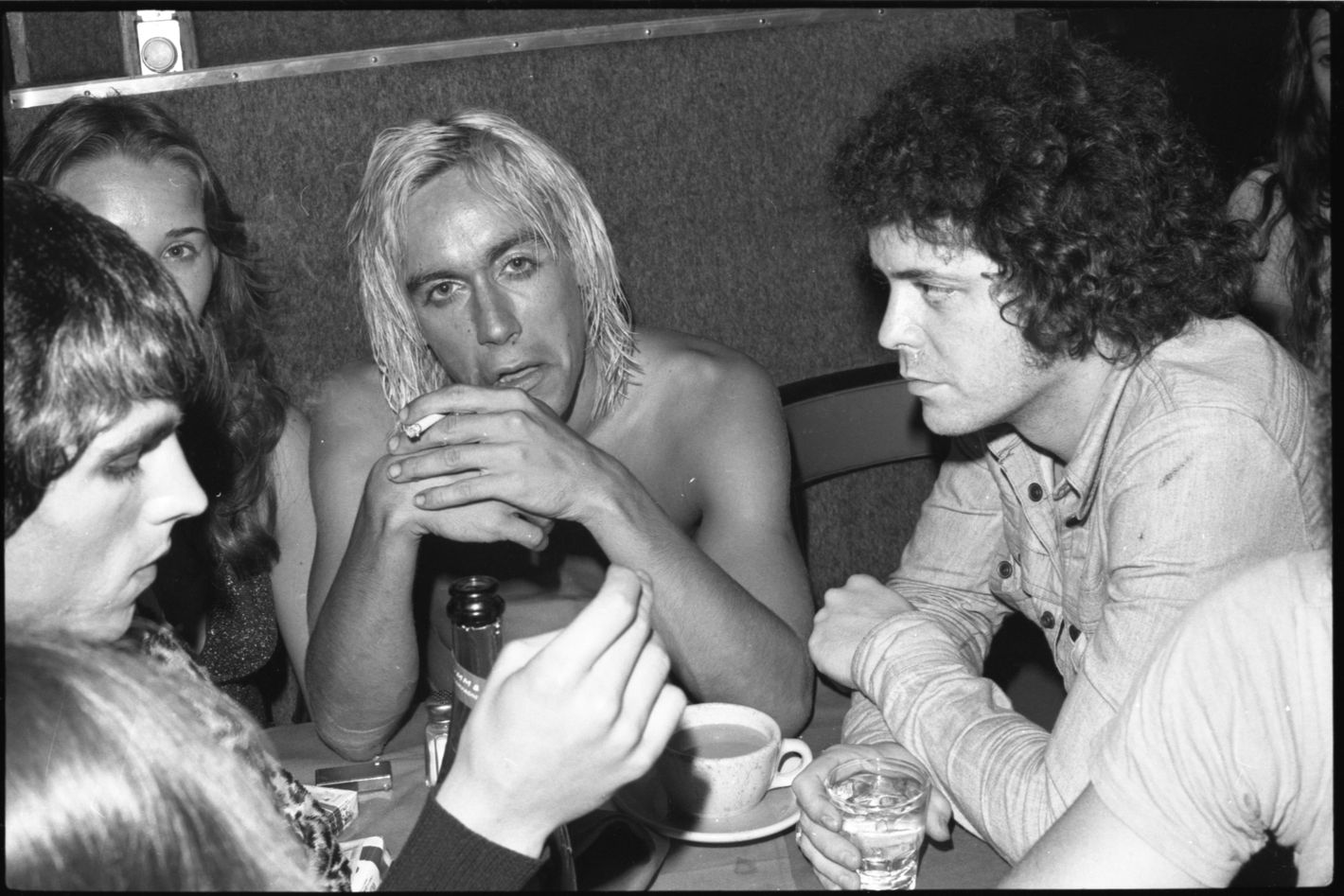

Nothing Has Captured the Mystique of Max’s Kansas City

Photo: Danny Fields/© Gillian McCain

Photo: Danny Fields/© Gillian McCain

For New York’s anniversary, we are celebrating the history of the city’s restaurants with a series of posts throughout the month. Read all of our “Who Ate Where” stories here.

In the late 1960s, a ruby-red, pencil-thin laser beam, quivering with particles of soot and smoke, emanated from a second-floor loft window at Park Avenue South and 19th Street. It was a light sculpture called Laser’s End by an artist named Frosty Myers, and it was aimed two blocks south through a hole cut in the awning of Max’s Kansas City, where it was caught by a small mirror and bounced through the plate-glass front window into the restaurant, penetrating a layer of cigarette smoke that hovered above the long front bar, three deep with painters and artists, passionate and stoned, drunk and argumentative, past John Chamberlain’s crushed automobile, beyond the phone booth and the small toilets, past the swinging doors to the kitchen, and landed on the rear wall of the back room, where the beam shimmered like a stoned-out star of Bethlehem. “Truly, the FBI would have done well by itself to close the place down,” Frosty Myers once told the New York Times.

Max’s Kansas City was Café Deux Magots on speed, a petri dish of art and pop culture, poetry, gender experimentation, and drugs. It’s the subject of books and articles and photo essays, all of which have tried but failed to capture its mystique. It was lightning in a bottle. A folle pensée. The back room, the center of the action, was a windowless cul-de-sac, no more than 30 by 25 feet, with rough gray carpeting up the walls. It was nicknamed the “Bucket of Blood” because the ether itself seemed ensanguined by a sculpture of four red neon tubes over a booth in the corner. After you were there a few minutes and your eyes adjusted, there were no colors, only black and red. The regulars who sat in the corner booth below the sculpture would sometimes stick their chewing gum on the neon lights, which mightily pissed off the artist, Dan Flavin, whose estate, 30 years later, sold a copy of the sculpture at Christie’s for $662,000.

While there was no velvet rope at Max’s, there was a nasty little woman known as Tiny Malice who sat on a barstool just inside the front door to keep normal people out, which she did with a simple “You don’t belong here. Get the fuck out.” Max’s wasn’t just clubby; it was tribal. Strangers were repelled or killed. The energy in the back room was kinetic and rubbery, people bouncing off the walls, skittering table to table, drink to drink, drug to drug, ashtrays filled with endless smokes and bumming of smokes, an occasional hand job under a napkin, a blowjob under a red tablecloth. There were poets, alcoholics, junkies, speed freaks, misfits, mainliners, rock stars, occasional movie stars, psychos, lost souls, scions, broke writers, and broken painters. There were drag queens who were like X-Men, dissolute heiresses, a baby elephant (once), Jane Fonda and Roger Vadim (once), Andy Warhol (almost never), and all the Warhol martyrs and superstars, many of whom were doomed to overdose or suicide. There was Patti Smith, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Fran Lebowitz. There were also waitresses with attitude, dressed in black micromini skirts, frequently without panties, sometimes with a tampon string showing. On each table there was a small bowl of dusty white chickpeas that would break your tooth if you bit one. Instead, the chickpeas were used as projectiles when a war of chickpea snipers broke out, like a low-key food fight in a high-school cafeteria.

Although the logo boasted “Steak Lobster Chickpeas,” and the $8.50 club steak was a bargain, as were $3 bottles of burgundy, people didn’t go to Max’s for the food or fine wine. Max’s Kansas City had nothing to do with Kansas, nor was there a Max, but there was Mickey Ruskin, a big shlumpy guy in ill-fitting clothes, grizzled, stringy hair, and a chipped front tooth covered in a fuck-you gold crown so when he smiled he looked like a Jewish pirate. He was a Cornell-educated attorney who gave up law to buy a coffee shop in the East Village where he nurtured a bohemian clientele of threadbare poets and painters. A few coffee shops and one steak restaurant (the Ninth Circle, before it was a gay bar) later, Mickey opened Max’s in 1965. From the start, he let his regulars run up tabs when things were tough, and they paid him with their poems and their art, now probably worth tens of millions of dollars if he had hung on to them, including work by Andy Warhol, Carl Andre, and Frank Stella.

Occasionally there was “Showtime,” a spontaneous piece of performance art indigenous to the back room with the instigator standing on a table. Typically, a woman named Andrea Feldman, with scraggly blonde hair and Cleopatra kohl eyes, on a mix of Seconal and psychosis, climbed up on a table holding a Champagne bottle and cried out “Showtime!,” eliciting a round of hooting from the crowd. She pulled up her skirt and tried to insert the neck of the bottle through a tear in her panties, to cheers and applause. She began to sing an unintelligible song, drowned out by laughter and shouts, when Mickey Ruskin rushed into the back room, looking like he was the high-school principal who caught students smoking in the bathroom. If Mickey caught you standing on a table doing “Showtime,” he put you in detention and banned you from Max’s for a couple of days or weeks. But if you were a regular, he would always relent.

The rock-and-roll world slowly took over Max’s and the artists and the backroom freaks that made the place so unusual stopped coming. Mickey closed Max’s in December of 1974. It reopened as a rock-and-roll club in 1975, but it was never the same. Mickey Ruskin died in New York City on May 16, 1983, at the age of 50.

More on ‘Who ate Where’

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.