when you want, where you want.

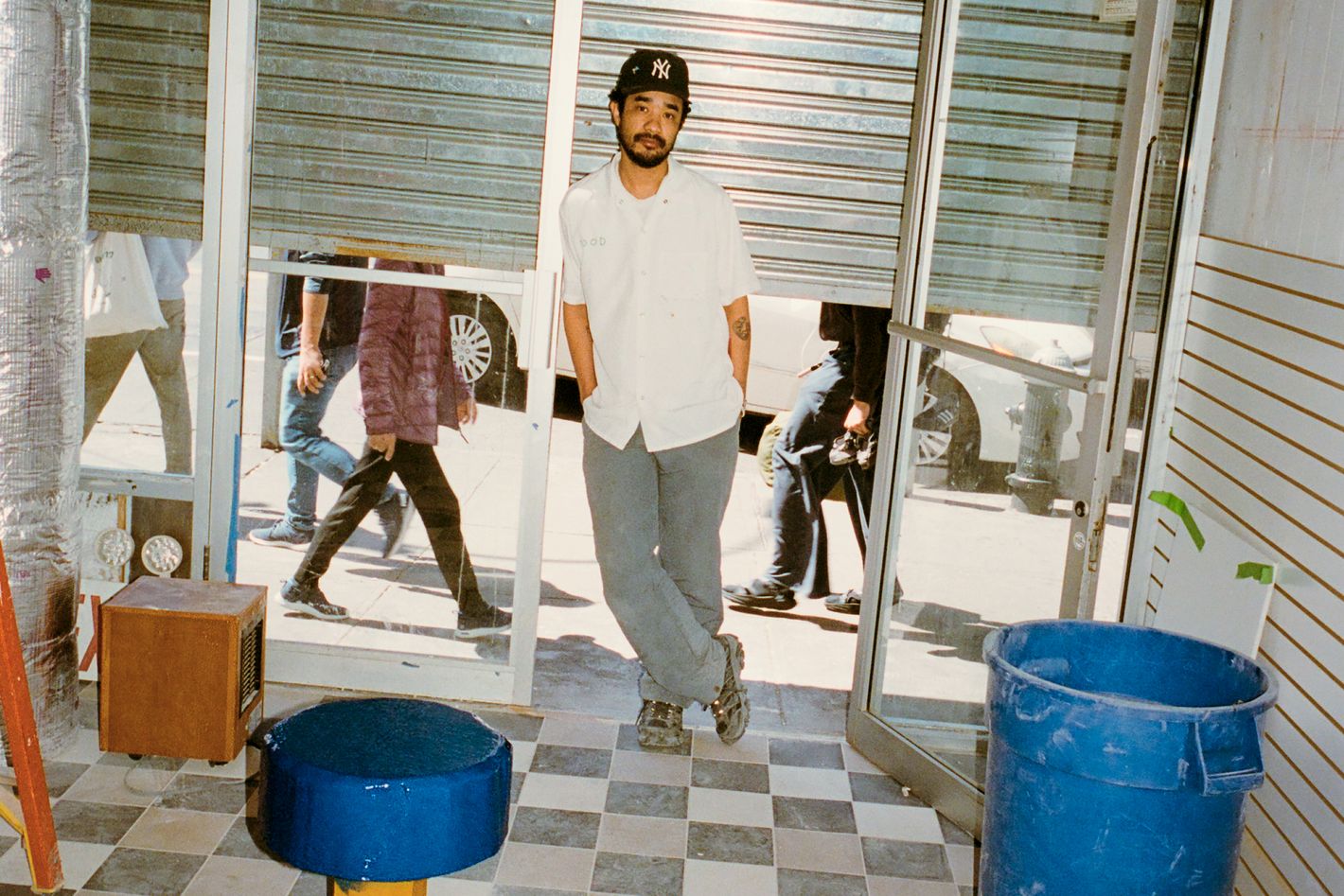

Lucien Smith Gets a Job

Photo: Zander Taketomo

Photo: Zander Taketomo

No one would accuse Lucien Smith of being original, least of all Smith himself. “I’ve always role-played as a painter, role-played as a fine artist,” he says, swiveling in a chair in his studio. “I don’t know how much of it is genuine and how much of it is an act. Maybe the whole thing.” His earliest public role was wunderkind, which he took on in 2011 when he shot out of art school, Supreme beanie askew, and started selling work that flipped at auction for nearly $400,000. His first big sale was a landscape he copied from Winnie-the-Pooh, and his first big series comprised splatter paintings made by spewing paint from a fire extinguisher. Those brain-dead Pollocks begged critics to slot him into a trend they called Zombie Formalism, a decorator-friendly aping of mid-century abstraction. Smith, who is affable and casual and now makes airbrushed paintings of celebrities’ faces, welcomes comparisons. As we sit in his tall-windowed, high-ceilinged Chinatown loft, he lists off the artists whose careers he thinks he might have had if he’d kept up his momentum (Rashid Johnson, Jeff Koons, Cecily Brown), the ones whose careers he doesn’t want (Damien Hirst), and the ones he might be channeling (Andy Warhol). “Maybe everything is derivative, you know?” he says with a smile. “Maybe we’re all just living the lives of other people.”

Smith is 36. After a decade-plus of spinning his wheels — during which he dated and broke up with Marlene Zwirner, partied, quit his galleries (or was fired by them), watched his prices tank, partied more, moved to Montauk, moved back, and got into crypto — he says he’s ready for his next act. In June, he’ll soft-open a restaurant called Food, named after the legendary artist-run restaurant that opened in 1971 and is woven into the history of the Soho loft scene. Smith says he wants his Food to pick up where the first Food left off, such as by hiring a bunch of artists to work there. The original was founded by Carol Goodden, a dancer and photographer, and her then-boyfriend, the late artist Gordon Matta-Clark. With regular hours and a huge cast of occasional workers, it operated as art-world employer, cafeteria, and de facto meeting spot for everyone from Trisha Brown and her dancers (of which Goodden was one) to Philip Glass’s collaborators. The new Food is being opened by Smith, a creative director and producer named Ken Farmer, and Laurence Chandler, a menswear designer who used to manage Ye’s brand, Yeezy. The original was born on Prince Street at a time when working a couple of shifts a week might cover your loft’s rent. The new Food will be in Dimes Square, two blocks from a luxury hotel. Smith says that no matter how “corny” anyone thinks it is, Dimes Square is for artists. “This is my Soho,” Smith says, “and I’m very into it.”

He leads me down the stairs of his studio building, out the door, and a few steps down Canal Street to the corner of Eldridge, where he rolls up the gate of a former dumpling restaurant. This will be Food. Right now, it’s a construction zone with a newly installed HVAC unit coated in a thick layer of dust. Smith wants to reserve the summer for experimentation. He’s not afraid of failure; in his view, he already failed as an artist because he never figured out a sustainable practice. “I had an unrealistic first exposure to success,” he says. “For at least five years of my life, I was like, I want my 20s back. And I kind of didn’t do anything, and that was great, and then it became boring. Then I was like, I want my career back, but fuck, pissed it down the drain.” He’d learned about Food while studying at the Cooper Union, and around five years ago he started thinking someone should revive it. Smith is a streetwear guy with collabs logic — he has modeled for Supreme, and Virgil Abloh made a shirt with one of his paintings on it. So at first, Smith tried to get Ye involved. Chandler was one of his collectors and he knew Yeezy was exploring the possibility of culinary projects, so he suggested to Chandler that they open Food under Ye’s brand. “I was sending him all of this Food stuff, like, ‘You got to show Ye this. If you guys open a restaurant, I’ll come work for you,’” he says. (Chandler says he never proposed this to Ye.) After Ye fired Chandler in 2022, Smith texted Chandler, “Yo, I still want to do this Food thing.” Smith says Chandler handles the financial stuff and finds investors and partnerships; despite Smith’s self-described talent for self-promotion, he says he is not used to asking people for money.

The original Food, which Goodden ran for about two years, would not have opened at any other time. Its whole DIY spirit hinged on being part of Soho’s postindustrial era, when there were hardly any eateries nearby (besides Fanelli’s) but there was plenty of raw space. Much of what made Food unique — that it employed a lot of artists, served seasonal food, and invited guests to curate dinners — has since been absorbed into the logic of special little downtown restaurants. So why, aside from the branding exercise, did Smith want to use its name? He says only that “it wouldn’t have been fair for me to open an artist-run restaurant without giving some credit to that original idea.” Jessamyn Fiore, a curator and co-director of the Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark who’s seen artists stage dinners in tribute to Food everywhere from Arkansas to Dubai, says she doesn’t know of anyone who has attempted a recreation in the form of an actual restaurant. Fiore’s mother, Jane Crawford, is Matta-Clark’s widow, and Fiore, who has a different father, grew up in the East 20th Street loft that Crawford and Matta-Clark set up together. Fiore says Chandler and Smith sought her input early on. “Lucien is giving it his own spin,” she says. “I mean, I’m a curator. It’s not for me to tell an artist what their vision is.”

Food 1971 had an airy, wood-table aesthetic, built out by artists including Goodden, Matta-Clark, and the Louisiana-born Tina Girouard, who became an integral part of operations and would sometimes cook Cajun-inspired dishes. Food 2025 will be a long, counter-service space envisioned by industrial-design guys. The stools will be glossy epoxy in assorted colors and designed by the British artist and designer Max Lamb, who’s known for wacky chairs; there will be one banquette in the back designed by Swiss brand USM. Although some may say the point of Food was its social scene, Smith initially wanted his version to be available solely as a delivery item on Uber Eats, a service he loves. “I wanted to be able to post, like, ‘This is going to be on Uber Eats tomorrow,’ and it’s something bogus, like a fried PB&J sandwich,” he says. But it turned out an Uber Eats Food was “a hard concept to raise money against.”

Smith, whose restaurant experience is limited to a middle-school summer job at a pizzeria on Fire Island, says he’ll be Food’s director. Since every person who works there — including him — will be cooking and serving meals, he thinks every item on the day menu should be as simple to prepare as a Chipotle bowl; he plans to offer a curry or stew of the day priced at around $8. He says it might turn into an ice-cream parlor for a while this summer and jokes that he’s starting the restaurant because he doesn’t have a kitchen in his studio. When I ask for an example of what else he thinks Food should serve, Smith says, “Chinese chicken salad. Like, you really can’t get that salad anywhere in New York.” (The night menu will be fancier, courtesy of French chef Mathieu Canet.) He also wants to hire a rotating cast of around 80 artists. Could that make the quality of the cooking inconsistent? He shrugs. “Things like consistency are what have defined a successful restaurant, but the success rate of restaurants is low,” he says. “So maybe consistency isn’t a winning thing. Maybe inconsistency is something a restaurant needs.”

It’s true that Food was never supposed to be like other restaurants. Goodden says she and Matta-Clark came up with the idea at one of her dinner parties, and she financed the restaurant with a family inheritance. Goodden emphasizes they “didn’t know what they were doing. We simply did.” She calls many of her decisions “disastrous” — like the Spanish tile she wanted for the floor, which “echoed all the noise.” Or her insistence on serving fresh-squeezed orange juice, which meant someone had to spend all day squeezing it. With no experience running a business, she priced some items way too low and some way too high and sold bowls of soup at a loss. After about two years, she and Matta-Clark were ready to move on. Unable to sell the restaurant — no normal restaurant owners could understand what they were doing — they gave it to their most trusted assistant manager, who then ran off to Europe with all the restaurant’s cash. Somehow, Food survived under different owners into the ’80s.

Goodden, who is 85, now lives in New Mexico and trains horses. She says Smith reached out to her in 2023 and mentioned he was thinking about starting a restaurant. She says he did not tell her he wanted to call it Food. “It was framed in some vague statement, like there had been a spate of ‘new cuisine’ restaurants and he was tempted to start his own, so he was curious how my ideas had progressed,” she says. “The next thing I know, a friend of mine showed me a news story. And there’s FOOD, using our logo, all capitalized. I called Lucien and said, ‘What is this?’ He sent me pictures of the space, which looked really narrow to me.” She has chosen acceptance, she says, because “there’s no point in trying to stop it. He’s using our name and saying it’s a re-creation. I have pulled back from it. I wish him well.” (Smith says his team did tell Goodden he was relaunching Food before she saw the news story but acknowledges some details may have been “lost in translation.”)

The first Food might have been a business, but making money for its owners was not the point. For Smith, that is the point — he says it has to be. Recently, he’s been funding his various projects by selling some of his old artworks that he kept back from his galleries, “but that is running out.” He’s already dreaming about opening Foods in London, Paris, and Milan. “The original Food didn’t work, so I have to think like a capitalist and figure out how we keep this idea of ours thriving,” he says. “I have to think about scaling it.” When I suggest this may be in tension with the spirit of the original, Smith interrupts me. “Yeah, or not,” he says, widening his eyes. “That’s the thing. Or not. It’s this simple: There’s a counter. On one side, there’s people that work there; on the other, there’s people eating. The cost to make the food and pay people’s salaries is less than how much we make from people buying the food.” At the very least, he thinks it will be fun. “I’m excited to be behind the counter at 2 a.m. and make some monstrosity of a soup — or a great soup, depending on my mood,” he says. “People are surprised, but it’s exactly what I want to be doing: grounding myself in something like having a job.”

Related

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.