when you want, where you want.

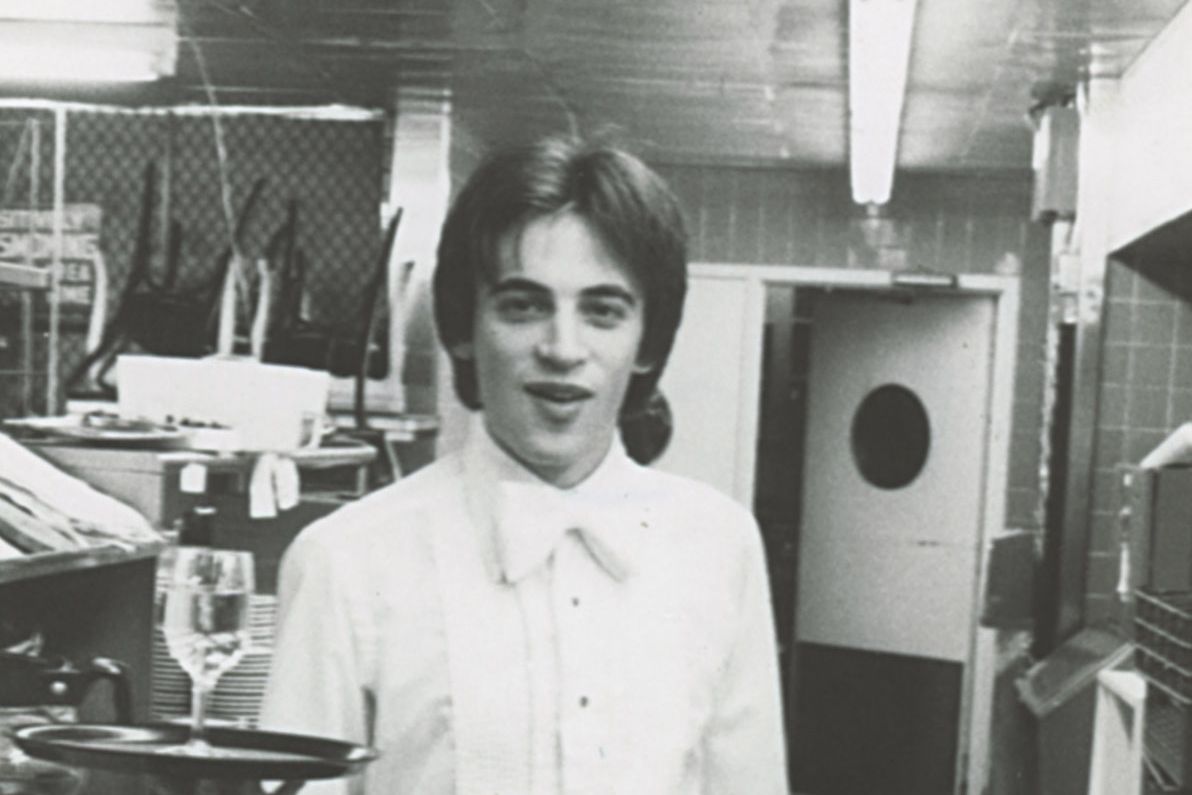

‘I Was 24 and Working Illegally’

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

It was October 1975. I was 24 and had arrived in New York with a vague plan to make films. Running out of money in the second week, I ditched the film idea and found a job as a busboy at Serendipity, the ice-cream parlor on East 60th Street.

Like many immigrants, my desire to live in New York came from watching films. One film in particular: Klute. There’s a terrific scene early on in which the two leads, Jane Fonda and Donald Sutherland, are out past midnight buying fruit from a sidewalk produce stand. As Sutherland reaches for some luscious-looking peaches, Fonda’s sexual desire for him explodes onto the screen. This was the exact moment when I longed to live in New York. But it wasn’t the scene’s eroticism that triggered the longing. It was the idea that you could buy fresh fruit in Manhattan after midnight.

The odd thing about experiencing New York for the first time was that it seemed more like the films than the films themselves. Places rarely live up to expectations, but New York did — particularly its element of availability. Unlike London in 1975, subways ran all night, bars served until 4 a.m., taxis were available 24/7, and diners never closed. Not that I needed to have an egg sandwich and a coffee at three in the morning, but knowing I could helped me sleep better. It still does.

Knowing I can do something, without necessarily doing it, is vital for me. There’s a scene in the film Pennies From Heaven in which an unhappily married man who’s fallen in love with a schoolteacher asks if she’d ever consider having sex with him on an elevator floor. He doesn’t want to have sex on the elevator floor, he just wants to know it’s a possibility. I feel that way about most things. (She says “yes,” by the way.)

I was working illegally and living in Queens with a couple of guys I’d met at a kibbutz three years earlier. New York was dangerous in the ’70s, and after leaving work at night, I’d stuff whatever tips I’d made into my socks and ride the 7 train to the last stop, Flushing–Main Street.

Needing extra money to rent an apartment in Manhattan, I found a second job as an oyster shucker at a downtown place called One Fifth. This stylish restaurant had recently opened on the ground floor of a 1920s skyscraper at 1 Fifth Avenue in Greenwich Village. With its Art Deco design, attractive floor staff, and artistic customers, One Fifth opened up a whole new world to me.

After shucking oysters for a month, I was promoted to waiter. Having a poor short-term memory, I was hopeless at the job. I’d often wake in the middle of the night remembering the two cappuccinos that table No. 12 had ordered nine hours earlier.

On my second shift, a busboy called Po Ming was assigned to me. Before the service began, I jokingly gave him an oversize cup for the supposed abundance of tips we were going to earn that night. Extending the joke, he silently exchanged the oversize cup for a large wine bucket. That was the moment when Po Ming and I became friends. Humor and integrity are two qualities I value above all others, and one rarely finds them in the same person. But this busboy from Communist China possessed both. Thirty-year-old Po Ming would soon become my closest friend.

Undeterred by my incompetence, One Fifth’s customers were surprisingly forgiving once they heard my English accent, and after six weeks of waiting tables, I was promoted to maître d’. I then realized that in America charm played a more important role than ability. Or could do, if you bought into it. And I bought into it big time.

One Fifth’s owner was a radiologist called George Schwarz. Schwarz was so passionate about food and wine that in the early ’70s, he began building his own restaurants. Although he had no experience in the business, Schwarz trusted his own taste and each restaurant he built succeeded beyond expectation, One Fifth most of all.

If only Schwarz had trusted his staff as much as his taste, One Fifth would still be around today. But he was so convinced his employees were plotting against him that Schwarz would find a reason to fire at least one of them every other week. Consequently, five months after being hired at One Fifth, I became its most senior employee working in the dining room.

For some reason, Schwarz took a liking to me. Born in Germany, he had a quirky sense of humor and seemed to appreciate mine. All the same, when he asked one night to have a word with me at the end of my shift, I felt sure I was getting the chop. Like an Academy Award nominee in reverse, I worked for hours on some disparaging last words. Yet instead of firing me, Dr. Schwarz promoted me to general manager.

I was 24 and working illegally but suddenly found myself being shot out of a circus cannon into this swanky Manhattan restaurant and being paid handsomely to manage it. On top of this, Schwarz promised to sponsor me for a green card. I couldn’t believe my luck. I still can’t. Which is why there’s not a day goes by when I don’t fear an authority figure tapping me on the shoulder and saying, “McNally, you’re a fraud. We’re putting you on the next plane back to London.”

I got to know George Schwarz and his wife, the painter Kiki Kogelnik, quite well. It’s not often one likes both partners of a married couple to the same degree. Half the married couples I’m friends with I dread seeing together. But I liked Kiki as much as I did George. In some ways, more so. Every other month, as a sort of field trip, they’d take me and a few other employees to dinner at a three-star restaurant. George analyzed every ingredient on his plate as if he were examining an X-ray. I learned more about food and wine from him than anyone else in the business.

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

In the precarious world of New York restaurants, One Fifth was something of a game changer. Its large, bustling dining room combined uptown glamour with downtown cool and was a forerunner to many future Manhattan restaurants, including many of my own. Though I’m loath to attribute changes in character to one pivotal moment — and am suspicious of people who do — I often wonder what turn my life might have taken if I hadn’t been hired at One Fifth. I think most events that have a significant effect on us are impossible to detect until years later. It’s only now, 40-odd years after working at One Fifth, that I realize what a huge influence it had on me. Especially in terms of design.

Professional designers like to say that good design “is all about the details.” This isn’t true. Good design is all about the right details. It’s also about what you don’t do, what you refrain from doing. Unfortunately, I don’t always take my own advice.

Good design, like good cinematography, should never strain to be noticed. It should appear natural and effortless. The moment a designer’s hand becomes conspicuous, the game’s up.

Restaurant design begins and ends with lighting. Working at One Fifth, I discovered that the less overhead lighting and the more side lighting one uses, the more attractive the dining room becomes. Having many different light sources at low wattage gives a room a terrific glow. But of course, seductive lighting doesn’t compensate for tasteless food or inept service. Likewise, extraordinary food, design, and service never guarantee a successful restaurant. Nothing does except that strange indefinable: the right feel. At its best, the right feel can transport a customer like nothing else. Without it, you may as well pack your bags.

For its first two years, One Fifth was the most fashionable restaurant in Manhattan. It opened several months after Saturday Night Live first aired on NBC, and the cast held their original after-show parties at the restaurant. After my promotion, I was responsible for organizing these charismatic events, and many would last until four in the morning (particularly if John Belushi was present). It was at one of these parties that I met SNL producer Lorne Michaels, whom I’ve remained surprisingly close to ever since. My son Harry was the ring bearer at Lorne’s wedding in 1991, and my daughter Alice was named after Lorne’s wife.

In the mid-’70s, singer Patti Smith and her ex-boyfriend, the photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, were regulars at One Fifth. Sam Wagstaff, Mapplethorpe’s benefactor and at one point lover, lived in an apartment above the restaurant, and all three of them would eat at One Fifth together a few times a week. They made an intriguing-looking threesome. While Smith and Mapplethorpe had the surly appearance of young, rebellious artists (which they were), the quietly understated Wagstaff — who was a former museum curator and exceptionally handsome — seemed to embody the patrician values of an earlier period. At the time, I found Wagstaff to be the most interesting of the three. I still do today.

On nights when Wagstaff wasn’t at the table, Smith and Mapplethorpe could be very difficult to wait on. Smith, unfortunately, was incredibly rude to the servers. It’s impossible for me to listen to a Patti Smith song today without remembering her reducing a waitress to tears because she forgot to put bread on the table.

Although Mapplethorpe, with his tough-boy leather-jacket image, could be terse with the servers, he never tried to belittle them the way Smith did. The only time I saw Mapplethorpe without his leather jacket — when the restaurant’s air conditioning broke down — he seemed strangely reduced and, like a policeman out of uniform, surprisingly ordinary-looking. Maybe it was a coincidence, but without the leather jacket he was also friendlier to the staff. Regardless of what he was wearing, Mapplethorpe was a brilliant photographer. However, I believe that without Wagstaff’s patronage, his photographs would not be as celebrated as they are today.

The last time I saw the urbane Wagstaff was on the subway. We rode ten blocks together on the Lexington Avenue line one evening rush hour. Our car was so full that we stood all the way. Though 63, he was still remarkably good-looking. It seemed incongruous to see someone this wealthy and refined riding the subway.

And although he didn’t know me well, Wagstaff graciously chatted throughout the journey. It was only after we parted that I realized he hadn’t said a word about himself. This was 1985. Within two years he would die of AIDS.

There are only two or three people in life that I wish I’d known better. Sam Wagstaff was one of them.

Not long after being promoted to general manager, I noticed something vaguely interesting about a young Englishwoman who came for brunch every Sunday. She was often accompanied by several writers and always ordered the same dish: eggs Benedict. One Sunday, she came in alone a few minutes after the kitchen had closed. Knowing she was a regular, I asked the brunch chef, Chang, to reopen the kitchen and make her eggs Benedict. Like most restaurant chefs at the time, Chang refused to cook the order because it was given to him one minute after closing time. I told him that the customer came every week and besides, she was quite pretty. On hearing she was pretty, Chang went bananas and threw his sauté pan at me. His aim was as bad as his cooking, and he missed by a mile. I picked the pan up off the floor, and for the first and last time went behind the kitchen line and cooked a customer’s order.

Although I made a hash of the eggs Benedict, the incident itself had rich consequences: The young woman was future Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour, and despite coming from opposite ends of the English class system, we became close friends. Nothing romantic happened between us, yet we’d often watch movies together in the afternoon, which, outside of the bedroom, is the most intimate thing two people can do at that time of day.

Despite my English accent and passing charm, not all of One Fifth’s customers liked me. A few days after I was promoted from waiter to maître d’, a fashion designer who was one of the restaurant’s regulars summoned me to his table. Wearing a fancy tuxedo (which I wouldn’t be seen dead in today), I went to the table expecting a question about the wine list. In front of his boyfriend, the fashion designer eyed me and sneered: “The worst thing this restaurant has ever done is to make you its maître d’.”

Oddly enough, the restaurant’s owner, George Schwarz, would eventually think the same.

As One Fifth’s general manager, I now had the responsibility of hiring the restaurant floor staff, which was absurd, seeing as I was illegal and had been working in restaurants for just five months. I was also hiring people whose jobs I knew next to nothing about. Only in America is it possible to get to the top of the heap without knowing anything about the job. (Some even become president.)

Two of the people I hired would play an integral — and often complicated — role in my New York life. One was my older brother Brian and the other was my future wife Lynn Wagenknecht.

Brian arrived in New York on Thanksgiving Day 1976. Since I was working that afternoon, he came directly from midtown’s Port Authority Bus Terminal to One Fifth to meet me. It was my 28-year-old brother’s first time in New York and also his first time in a restaurant this glamorous. He was stunned. He’d never experienced anything as sophisticated as downtown New York and was in awe that, in managing this stylish restaurant, I seemed to have a foot in the door of Manhattan’s high life. Though well read (much more so than me) and well traveled, Brian resented the fact that he was working class and longed to escape it. Superficially, New York gave him the chance to break free.

Over the next few weeks, I found Brian an apartment on Bleecker Street and gave him a job as a bartender at One Fifth. My brother was a terrific bartender, and it wasn’t long before he had an impressive following of downtown’s artists and intellectuals.

After a few months tending bar, Brian — like me — also had one foot in the door of the city’s smart life. The only trouble was that at times the opening wasn’t wide enough for both of us.

One day, while interviewing floor staff, I found myself sitting across from a 24-year-old woman applying for a waitress job. Her name was Lynn Wagenknecht. It was clear from her complete lack of guile that she must have been new to Manhattan. She was. Lynn had arrived in the city six weeks earlier from the Midwest. She had long blonde hair and eyes bluer than robin’s eggs. After five minutes, I hired her. After five years, I married her.

During the interview I discovered that after graduating from Stanford, Lynn had attended the University of Iowa, where she received her M.A. and M.F.A. She’d come to New York with aspirations to paint and perhaps eventually teach drawing at a university but meanwhile needed a job to pay the rent. Being hired by me led the educated Ms. Wagenknecht to exchange a noble life in academia for a lowbrow one in restaurants.

Apart from being the restaurant’s general manager, I was also its maître d’ three nights a week. This meant seating customers in the dining room, where Lynn was one of eight servers waiting tables.

Lynn was a brilliant waitress — she was also completely herself when waiting tables. I was so mesmerized watching this midwestern woman work that I quickly fell in love with her. (People become strangely appealing when performing a job with skill.) The only problem was Lynn wasn’t in love with me. Even so, she agreed to see me outside of work.

In the early days of our dating, there was such an imbalance of affection between us that, consumed with jealousy, I often refused to seat attractive men in Lynn’s section. Even unattractive ones. (When you’re eaten up with jealousy, all men become potential suitors.) I remember scanning the room one night and seeing only women seated in Lynn’s section. What excuse I gave the men for refusing them tables I’ve no idea. But as maître d’ of this hip restaurant, I had many difficult exchanges with customers. One busy night, I told a pushy New Yorker — a John Gotti look-alike — that there wasn’t a table for him.

“Do you know who I am?” he snarled.

“No, but I can find out for you,” I quickly replied.

After he threatened to break my legs, I found him a table tout de suite.

My worst mistake as maître d’ was failing to recognize Ingrid Bergman. One night, a middle-aged couple graciously asked me for a table. Because the dining room was full at the time, I asked them to wait at the bar and explained that I’d give them the next one available. The man took me aside: “You do know that the woman I’m with is Ingrid Bergman, don’t you?” Having no idea who Ingrid Bergman was (I somehow got her confused with Ingmar Bergman), I looked at the tall, sophisticated woman standing several feet from me and just repeated my spiel about waiting at the bar. The man looked me in the eye, turned around and left. A week later, I watched the film Casablanca for the first time and saw the most beautifully dreamy actress imaginable. I felt like disappearing down the closest manhole.

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

Photo: Courtesy of Keith McNally

Since the eggs Benedict incident, Anna Wintour and I saw each other regularly. In 1978, she moved to Paris to live with her boyfriend Michel Esteban, a French entrepreneur who’d made a fortune in the record business. After a few months — perhaps out of loneliness — she invited me and Lynn to join her for a week. Knowing that we were penniless, Anna paid for our airfare and hotel.

Anna and Michel took us for dinner every night, usually to some of the best brasseries and bistros in Paris — La Coupole, Allard, Chez René, Vaudeville, Au Pied de Cochon, Balzar. My favorite was a place called Chez Georges. I loved the smell of escargots drenched in butter and garlic, the look of the red banquettes, the scored mirrors, the handwritten menu, the waiters with starched white ankle-length aprons. Everything about the place stimulated me. Even the jug of pickled cornichons on the table. I ate ris de veau (veal sweetbreads) for the first time at Chez Georges, which for someone who’d grown up on a diet of boiled vegetables and tinned salmon was like manna from heaven.

Although the aesthetically pleasing world of French bistros was a million miles away from my Bethnal Green prefab, something about the experience at Chez Georges that night struck a chord.

By taking me to these incredible restaurants, Anna’s plan was to seduce me into remaining in France to work alongside her boyfriend. By the end of a long week of being treated to such terrific bistros and brasseries, I was thoroughly seduced: not by the idea of moving to Paris, however, but by the thought of returning to New York and, with Lynn and Brian building our own version of a Parisian brasserie.

In February 1979, I received my green card from the U.S. Immigration Service. After working at One Fifth for three years, I was now legal and free to do the one thing I came to New York to do: write and direct films. Except I didn’t have the balls, and so I remained in the restaurant business. Besides, Schwarz had sponsored me for my green card, and while Schwarz was difficult to work for, it didn’t seem right to leave him the second I became legal. Like many mentor-pupil relationships, ours was destined to end badly. A month after I got my green card, we had a fight over the bartenders’ schedule and I walked out.

Lynn and I decided to open our own restaurant. We were fed up slogging away for other people and were anyway bursting with restaurant ideas of our own. In the spring of 1980, we hit the streets looking for a space. The only area downtown we could afford was Tribeca, a neighborhood between Soho and the Twin Towers unknown to most people living above 14th Street.

The real-estate broker gave us a list of three available spaces. The first two were lemons, but approaching the third, I noticed a red neon sign that shone so brightly it could be seen from Kansas. This was Towers Cafeteria. The second we pressed our faces against one of its three enormous windows, Lynn and I knew we’d struck oil.

Within the month, we’d signed a 15-year lease and roped my brother Brian into being our third partner. It was Brian who came up with the idea of calling it the Odeon — growing up, our local cinema was the Mile End Odeon.

Between signing the lease for the restaurant and fixing it up, Lynn and I spent a week in New Orleans. While walking around a shady area outside the French Quarter, we saw a large ’30s-style neon clock in the window of a junk shop that looked perfect for our unbuilt restaurant. The only problem was there was a NOT FOR SALE sign in front of it. The eternally shy Lynn persuaded me to go in alone and make an offer. “Offer a hundred dollars but no more,” she advised.

Entering the shop, I faced an angry–looking man behind the counter. “I know the neon clock’s not for sale,” I began hesitantly, “but I’d like to make an offer of …” Before I could say “a hundred dollars,” he blurted out, “I won’t take a penny less than $25!”

That $25 neon clock was our first purchase for the Odeon and has been hanging in the same position on the wall next to the bar since October 1980.

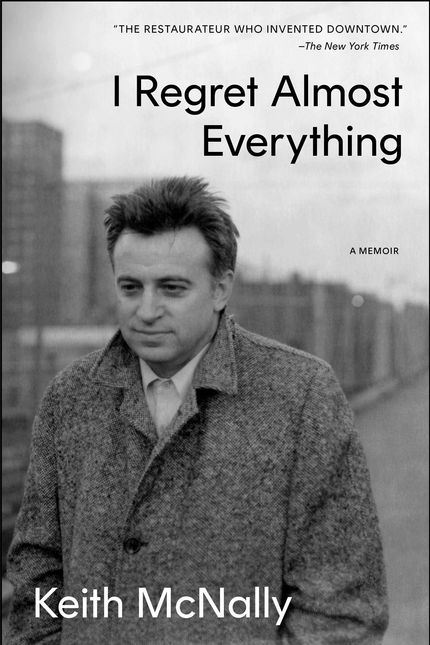

Excerpted from I Regret Almost Everything: A Memoir, by Keith McNally (to be published by Gallery Books, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, LLC). Copyright © 2025 by Keith McNally. Printed by permission.

Photo: Gallery Books

Photo: Gallery Books

‘I Regret Almost Everything’ by Keith McNally

Related

All Rights Reserved. Copyright , Central Coast Communications, Inc.